Umbria - The Green Heartland of Italy

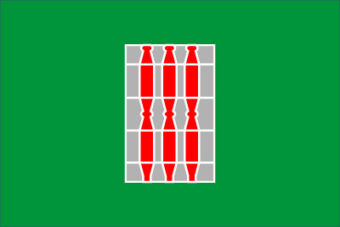

The Provincial Flag of Umbria

Geography

South Ridge of Monte Vettore

Umbria is bordered by Tuscany to the west, the Marche region to the east and Lazio to the south. Mostly hilly or mountainous, its topography is dominated by the Apennines, with the highest point in the region at Monte Vettore on the border of the Marche region. In literature one sometimes sees Umbria called "il cuor verde d'Italia" (the green heart of Italy). The phrase is taken from a poem by Giosuè Carducci.

The Tiber river forms the approximate border with Lazio, although its source is just over the Tuscan border. The Tiber’s three principal tributaries flow southward through Umbria. The Chiascio joins the Tiber at Torgiano. The Topino, cleaving the Apennines makes a sharp turn at Foligno to flow NW before joining the Chiascio below Bettona. The third river is the Nera, flowing into the Tiber further south, at Terni; its valley is called the Valnerina.

Poppies growing on an Umbrian hillside south of San Venanzo

History

The region is named for the Umbri tribe, one of those absorbed by the expansion of the Romans. Their language was Umbrian, one of the Italic languages, related to Latin and Oscan.

The Etruscans were the chief enemies of the Umbri, and the Etruscan invasion went from the western seaboard towards the north and east (lasting from about 700 to 500 BC), eventually driving the Umbrians towards the Apenninic uplands and capturing 300 Umbrian towns. Nevertheless, the Umbrian population was never eradicated in those conquered districts.

After the downfall of the Etruscans, the Umbrians attempted to aid the Samnites in their struggle against Rome (308 BC); but the Roman victory at Sentinum started a period of integration under the Roman rulers, who established colonies and built the via Flaminia (220 BC), the famous Roman “highway” which became a principal vector for Roman development in Umbria. During Hannibal’s invasion in the second Punic war, the battle of Lake Trasimene was fought in Umbria, but the Umbrians did not aid Hannibal against the Romans because they didn’t see being ruled by Hannibal to be any better than being ruled by the Romans.

During the Roman civil war between Mark Antony and Octavian (40 BC), the city of Perugia supported Antony and was almost completely destroyed by Octavian.

The modern region of Umbria, however, is essentially different from the Umbria of Roman times, which extended through most of what is now the northern Marche, to Ravenna, but excluded the west bank of the Tiber. Thus Perugia was in Etruria, and the area around Norcia was in the Sabine territory.

When Charlemagne conquered most of the Lombard kingdoms, some Umbrian territories were given to the Pope, who established power over them.

In the 14th century, the signorie arose, but were subsumed into the Papal States, which ruled the region until the end of the 18th century. After the French Revolution and the French conquest of Italy, Umbria was part of the ephemeral Roman Republic (1798–1799) and of the Napoleonic Empire (1809–1814). After Napoleon’s defeat, the Pope regained Umbria until 1860 when Umbria was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy.

The borders of Umbria were fixed in 1927, with the creation of the province of Terni and the separation of the province of Rieti, which was incorporated in Lazio.

Economy

The present economic structure emerged from a series of transformations which took place mainly in the 1960’s, 1970s and 1980s. During this period there was rapid expansion among small and medium-sized firms and a gradual retrenchment among the large firms which had hitherto characterized the region’s industrial base. This process of structural adjustment is still going on.

Umbrian agriculture is noted for its strawberries, melons, hazelnuts and walnuts, tobacco, excellent olive oil (often categorized as the best in all of Italy) and its vineyards, which produce excellent wines. Regional varietals include the white Orvieto, which draws agri-tourists to the vineyards in the area surrounding the medieval town of the same name. Other noted wines produced in Umbria are Torgiano and Rosso di Montefalco. Another typical Umbrian product is the black truffle found in Valnerina, an area that produces 45% of all truffles found in Italy.

The food industry in Umbria produces processed pork-meats, confectionery, pasta and the traditional products of Valnerina in preserved form (truffles, lentils, cheese). The other main industries are textiles, clothing (including very fine cashmere), sportswear, iron and steel, chemicals and ornamental ceramics.

For more information on Umbria visit: https://www.italia.it/en/umbria